Heribert Friedl: 100 Poems

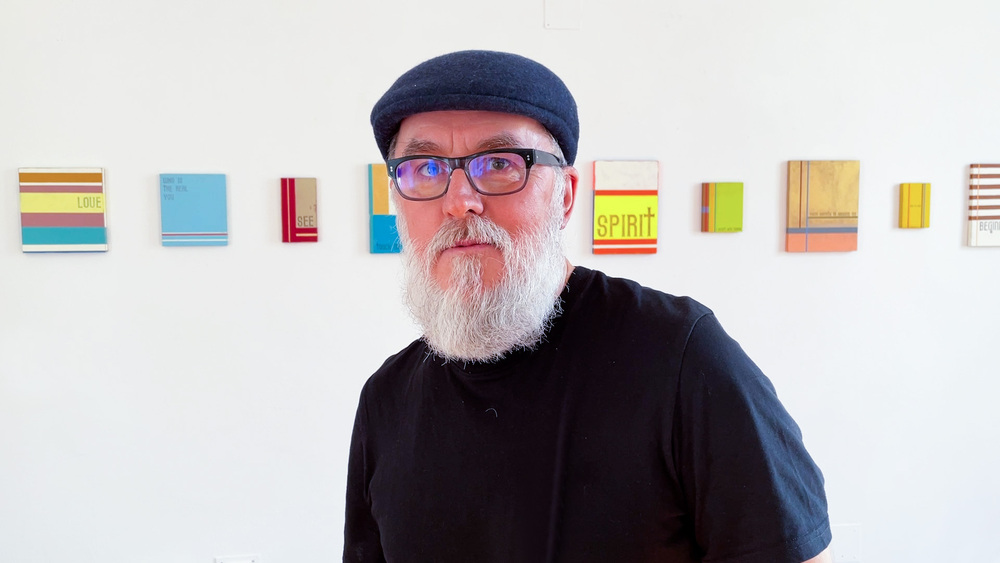

In this book, the 100 small pictures by Heribert Friedl, which for the exhibition at the KULTUMUSEUM in Graz were installed in the barrel-vaulted room of the former refectory in the old Minorite monastery in Graz, are archived as contemporary "devotional pictures". But there is no kitsch, no historicism, no world of yesterday preserved in this "prayer book"—on the contrary. The words, the sentences are drawn from pure life, its finiteness and how to overcome it, its hope and its talent for transcendence. As real pictures (works of art), these "writing icons" have a body whose edges are also painted—they are MDF wood panels and as such also have a corresponding weight. They are small pictures with balanced areas of colour that correlate with English sentences or words. The title of the exhibition refers to them as reduced poems, a hundred in number.

"Take yourself out, don't let it fill you up..., anyone can do that." Heribert Friedl said in an impressive conversation with curator Johannes Rauchenberger immediately after the exhibition was completed.

As the catalogue medium of the "prayer book" that the artist has chosen to document these images, it is reminiscent of a "Book of Hours" from a cultural and religious studies perspective. Books of hours in the late Middle Ages were adorned with the most precious illuminations by the best illustrators and represent special documents of a religious high culture as well as a very personal piety. In terms of religious history, this is a genre of books that, in accordance with (Christian) prayer practice, contain texts that structure the day: psalms, scripture readings and hymns. In monasteries, they are of course still maintained and cultivated as books. But in individual practice, the medium of the "book of hours" is increasingly giving way to the digital one: even people who have committed themselves to regular prayer by profession are increasingly doing so digitally.

What we find here is fundamentally a reverse process: from a digital auxiliary medium back to analogue time and the analogue body. And thus also a conscious use of time, the reduction of speed, the praise of repetition—but not in the sense of increasing the number of hits, but as an act of existential stabilisation that goes hand in hand with lamentation, memory, confidence, hope and consolation. When time is experienced in this way, something like "faith" becomes visible in Heribert Friedl’s pictures in the form of old, stable, enduring images. This is a quite extraordinary phenomenon, because "faith" in particular is usually something so alien in contemporary art production and, if at all, something so intimate that there is hardly any existential thematisation in the pictorial mode that is free of kitsch, irony or biting criticism. It is different here.

In Heribert Friedl's work to date, the analogue in the form of real images has seldom played a role. Rather, "ART IS NONVISUAL"[1] has always been his motto. Heribert Friedl has always critically scrutinised texts and images in these times of total digital overstimulation and image overload. He does this in a thoroughly ironic way: Friedl had already been digitally present in parallel to his exhibitions for a long time in the 1990s, with his website, which had the URL www.nonvisualobjects.com (and still does today). This creative term has been Friedl's guiding principle since 1996. In contrast to today, back then NOTHING was visible when you called up the website. As I remember from our first conversation, the artist was interested in the invisible. Hence: the invisible page—the contents of which only revealed themselves when you clicked the mouse. Hence: the white museum wall, whose images could only be seen if you evoked perceptions beyond the purely visual. And this essentially includes the scent. Friedl also took part in the "1+1+1=1 TRINITY" art competition at KULTUM in 2011. Coils of copper pipes were placed in the room as a sculpture, and when you operated the bellows with your feet, a fragrance was released—this work has been part of the KULTUMUSEUM[2]ever since.

More than 20 years ago, I exhibited his work for the first time at the KULTUM on the occasion of "Graz 2003—European Capital of Culture", as a representative of artists who had gained a foothold in the world with a special "approach" to art but had left Graz in the process. The exhibition was called "EX Graz". Friedl presented only white walls in an exhibition cell, there was literally nothing to see. But if you came closer, you could smell the surface; different scents structured the white surface.

Heribert Friedl has expanded his design repertoire over the years—he has worked with clothes that are documents of time and transience, of closeness and beauty, of scent and dirt: Most recently in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Admont Abbey, where he drew a "portrait of a most beloved person in the world and beyond" (2022) with a vast number of items of clothing, shoes, ties and scarves. But he also worked with sound, in 2020 in the Ursuline Church in Linz or in 2021 in the Mariahilferkirche in Graz for "Breathing In – Breathing Out", the exhibition during the coronavirus pandemic, which was also the exhibition for the reopening of the redesigned Minorite Centre: in a delicate, restrained manner, he composed a sound installation whose components are the bellows of an organ, a drop of water, rain and a dulcimer. "Tears of c" attempts to approach the theme of the breath of life both sonically and metaphorically. The breathing of the wind instruments was musically interwoven with the sound of rhythmically passing time. According to the artist and composer, the tears, sadness and pain in the form of drops of water and rain were due to the coronavirus period, which confronted people with their own and others' finiteness on such a massive scale. The music connected intensely and existentially with the place and its prayers, fears and hopes that had been captured over the centuries. At the same time, it was as if Heribert Friedl added something conciliatory to the heaviness with the overtones of the sound of a dulcimer. Whatever it was—a requiem, an invocation, a prayer: Breath was always linked—dum spiro, spero—with hope.

Heribert Friedl takes up this trail in the "100 POEMS"; now, however, he simply paints visible, tangible, haptic pictures, completely beyond his previous artistic practice. They have been created in three intensively designed "work blocks" of "PAINTINGS", which are called WIENER BLOCK (2022) and HINDINGER BLOCK I+II (2023) in the "working title". All three have a dedication: "Dedicated to Karl".

I can't remember ever before having offered an exhibition to an artist so spontaneously—especially as the planning for exhibitions takes a very natural amount of time. Nor can I remember being so "surprised" by paintings in my own view—perhaps the last time was when, as a young art history student at the Tate Modern in London, I was thrust into the room of "Mark Rothko paintings" (the paintings that Rothko originally painted for a restaurant but then withdrew). The colour surfaces of the Mark Rothko paintings, their overwhelming effect on the viewer, the immersion in a diffuse, imageless world, have very little to do with the paintings here, especially as those are large, oversized and billowing, while these are small, most of them smaller than DIN A4 and lined up in the exhibition in the large exhibition space in the historical ambience of a former monastery refectory. They are once again reduced in size in the booklet published for this exhibition; they take on the character of devotional images and the appearance of an artistic "prayer book".

Experimenting with the small format of a solid MDF wood panel leads the artist to colour organisations of surfaces, which he inscribes with words, board by board, always in the same—but differently sized—font, which refers to a different time in its cut.

The "Book of Hours" that we hold in our hands as "users" contains invocations, self-affirmations, promises, descriptions of states and expressions of gratitude from the very first variants—in the VIENNA BLOCK. In fact, just as the state of prayer has been known since man's gift for transcendence. The "YOU" referred to is initially the "YOU" lost through death; the request to come with him again when no one is physically there anymore, the announcement to "be here", the promise to be "YOUR MEMORY, YOUR MUSEUM", the pain of not being able "TO DO IT ANYMORE", the weeping for the other, the painful feeling of missing, the uttering of the word "LOVE", the promise to switch OFF and ON, the calm, the desire, the selflessness, the silence, your smile, a "THANK YOU". However, all of this is not simply a biographical processing, but rather a general experience where everyone "turns off" at different words. And comes to the realisation: "THE WORLD IS YOU". Suddenly, the experience, the certainty: "There is more". "There must be more." But at the same time the pain: "WHERE ARE YOU?" And the realisation that "YOU ARE MY MEMORY", "I AM NO LONGER YOURS"." Such a presence soothes.

Heribert Friedl told me about the process of creating these paintings that he experienced the words and sentences as inspiration—like a "pressure wave"—from which these linguistic condensations of immense simplicity and beauty then emerged. This resulted in intensive painting phases lasting several weeks in his studio in Vienna and on a farm in Hinding, Bavaria, from each of which three blocks of works were created.

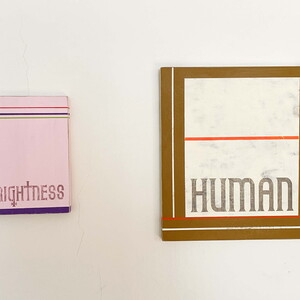

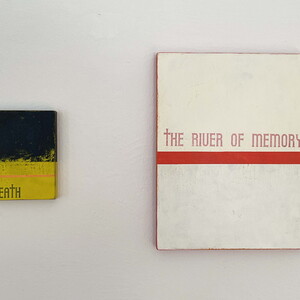

Gradually, the grief, which was initially very strongly processed, sinks to a deeper level, which increasingly has the character of carrying and being carried. Individual words such as "DEATH", "FAITH", "GOD", "HEART", "HOME", "LIFE", "TRUST" are used. Memories of the "ENDLESS SUMMER" and the "BRIGHTNESS" come up again and again, a feeling of being able to let go ("YOU CAN GO THERE") spreads, a feeling of gratitude sets in, a kind of self-assurance of no longer complaining, of gradually "KNOWING HOW LIFE GOES (AGAIN)", a small form of security for one's own self. These are quasi "recited" sentences for this self that is precarious and still wounded: "I accept 'it' with an aura of gratitude." "I AM A PART OF YOU." "I AM YOU." "I HEAR YOUR VOICE". The still grieving self says this "slowly and carefully" to itself; it can also "speak without words". This is already another speech, an appeal, similar to: "LOOK AT ME." This is still an appeal to the lost you, but perhaps also a gained one, in the sense of a transcended you. It is also an encouragement from there: "LISTEN TO YOURSELF."

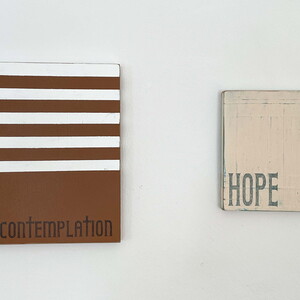

In the last work block of these paintings, which can be described as "written icons", the existentially elaborated mourning of the series painted so far, which already had the increasing character of a transcended "you" experience in the first HINDINGER BLOCK—with salutations, invocations, thanks, questions, almost praise—is transformed into a silent generality. There are no more sentences, no more questions, no more assertions, no more assurances for oneself, there are only individual words that describe something and at the same time everything that life would be, is or will be capable of, with its longing, origin, ability to relate, its emotions and the hope of a wordless understanding: "SOMEWHERE", "BEGINNING", "CONTEMPLATION", "CORRECTION", "DREAM", "END", "ETERNITY", "EVERYTHING", "EXISTENCE", "FATHER", "FEAR", "FEELING", "HEARING", "HEAVEN", "HERE", "HOPE", "JOY", "TENDERNESS", "MERCY", "MOTHER", "NOTHING", "NOW", "LOOK", "SIMPLICITY", "ONCE", "SPIRIT", "TOUCH", "UNDERSTANDING", "WORDLESS".

Heribert Friedl's—to use this word again—"Written Icons" are at the same time what the title claims to be: Poems. Writing has recently become a new form of artistic expression for the artist. Thus, both pictures and colourfully designed book pages are bound together in this "booklet". As pictures, they have a sensual materiality that is able to convey what is often no longer possible to convey: an experience of deeply felt faith. Friedl is fascinated by reduction and is able to show that where there is nothing, infinite greatness shines through, in the spirit of what Simone Weil wrote about the interpretation of images: "There is only one way to understand images—not to try to interpret them, but to look at them until the light suddenly dawns."[3]

Behind the zero point, the whole opens up. The pictures are an encouragement to stop ignoring as much as before and to familiarise ourselves with the question of where we can go when everything has been taken from us and when there seems to be nothing left.

The artist believes that everyone can do this: "Don't let yourself be buried, get out when you need to, listen in, only do what is really necessary: everyone can do this, even if we are all integrated into systems..."[4] Heribert Friedl has written "love letters" that transcend life and death. Each of these pictures is a book that breathes.

Johannes Rauchenberger