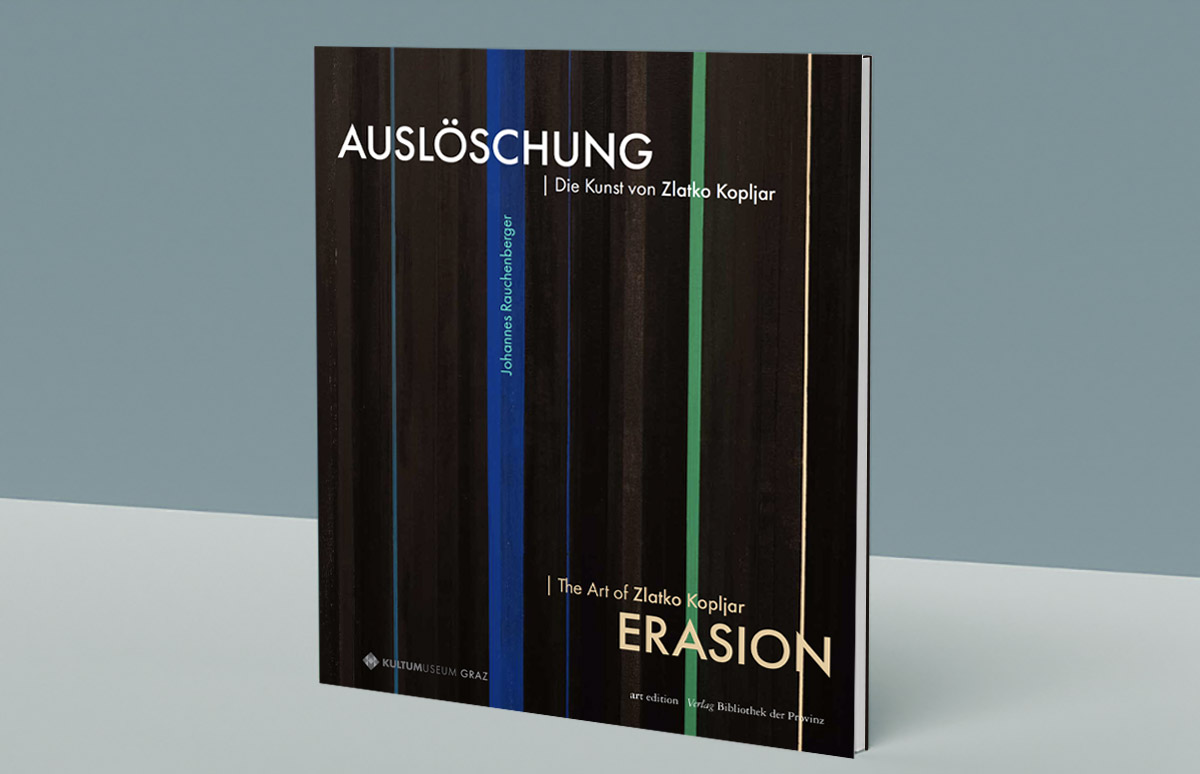

Zlatko Kopljar: AUSLÖSCHUNG | ERASION

English

|

|

| Hof vor dem Minoritensaal: K19 |

|

| EG: Kleiner Minoritensaal: K15 |

|

K15, 2012, (Videostill), HD-Video, Dauer: 4‘ 22“K15 ist eine Nachstellung des historischen Kniefalls des ehemaligen deutschen Bundeskanzlers Willy Brandt an der Gedenkstätte der Opfer im früheren Warschauer Ghetto im Jahr 1970. Der Künstler greift auf dokumentarisches Material zurück und rekonstruiert das ikonische Bild als Reenactment: Er selbst spielt in seinem Astralanzug, den er nun zum dritten Mal trägt, den deutschen Kanzler. Die Inszenierung wird in das nächtliche Ambiente des modernen Warschau verlegt, und wir verfolgen die Handlung von der Ankunft des Zuges, dem Aussteigen Brandts aus dem Zug, dem Besuch der Gedenkstätte bis hin zur Kranzniederlegung und dem schweigenden Niederknien des Bundeskanzlers inmitten von Menschenmassen, politischen Würdenträgern und Reportern. |

| 2 OG Süd – Treppe: Shame |

Shame (Scham), 1996, Fotodokumentation der Raum-Installation, Zigarettenpapier, Installation mit variablen Abmessungen

Die historische Passatacqua-Treppe vor der Jesuitenkirche St. Ignatius in Dubrovnik ist der Boden für eine frühe performative Installation des Künstlers: Er bedeckt sie mit zartem Zigarettenpapier. Ganz in weiß gehüllt ist sie der neue Boden für die Schritte der Darüberlaufenden. Die jahrhundertealte Oberfläche des Untergrunds nimmt viele Generationen mithinein, die hier privat oder öffentlich gegangen sind – in Form von Prozessionen, feierlichem Schreiten (etwa als Hochzeitspaare), herrschaftlichen Gesten oder einfach einem simplen Gehen. Die Fußabdrücke, die nun auf dem Weiß mit seiner symbolischen Anmutung wie Unschuld, Stille, Hochzeit, Ostern sichtbar sind, weckt alle Formen von Verschmutzung. Gleichzeitig ist der Untergrund dabei alsbald gerissen: Auf diese Erfahrung, dass der weiße Boden im Betreten reißt, bezieht sich der Titel Scham. |

| 2 OG Süd – 1. Ausstellungsraum: Vinculum |

|

Im ersten Raum des für Ausstellungen wieder neu eingerichteten Südflügels im Minoritenzentrum – bis 2009 war hier das Kulturzentrum bei den Minoriten untergebracht – ist erstmals in der Ausstellung in dieser frühen Arbeit Kopljars eigener Körper zu sehen:

Zlatko Kopljar: Vinculum I, 1995, Männliche Schaufensterpuppe: Beine, Hose, Schuhe, Perlen, Baumwolle, blaue Flüssigkeit, rundes schwarzes Glas, Ausstellungsansicht: Zlatko Kopljar: AUSLÖSCHUNG | ERASION. KULTUMUSEUM GrazDer schwarze (und dann später leuchtend weiße) Anzug wird später zu einem Markenzeichen seiner Performances. Dem schlanken, jungen Mann fehlt freilich der Oberkörper, dafür hat er Antennen an seinen Füßen.

Zlatko Kopljar: Vinculum II, 1995

|

| 2 OG Süd Gang I: Sacrifice of Isaac |

|

Unmittelbar nach der Vollendung seines Studium begann der Krieg in Kroatien: Zlatko Kopljar erinnert in der frühen Arbeit Sacrifice of Isaac dabei verstörend an das Opfer Abrahams (Gen 22). Religionsgeschichtlich wird die in Genesis 22 geschilderte Szene als das Ende der Menschenopfer für die Gottheit angesehen. Aber ist es dabei geblieben? Warum hat Gott heute – beim Morden und Opfern der eigenen „Söhne“ – nicht eingegriffen wie einst in der Bibel? In Zlatko Kopljars Abrahamsopfer-Bearbeitung geht es schlicht um den Mut, offensichtlich sinnlose Opfer, in welchen Namen auch immer sie gefordert werden, nicht zu vollziehen. Kunsthistorisches Vorbild war das Bild Caravaggios in den Uffizien. Doch dort hält ein Engel den Opfernden ab – bei Kopljar ist es nur der Blick nach Außen zum Betrachter. „Ich glaube nicht an Engel“, sagt der Künstler. „Aber ich glaube an den Mut, an die Courage, es nicht zu tun.“

|

| 2 OG Süd Gang II: DSASFSI,UE? |

|

Der Krieg in Kroatien hat gerade begonnen: In Erinnerung an Joseph Beuys‘ Performance von 1970-72 mit dem Titel: DSASFSI,UE? (Dove sarei arrivato se fossi stato intelligente? – Wo wäre ich hingekommen, wenn ich klug geblieben wäre?) stellt sich Zlatko Kopljar in jenen Tagen erneut die Frage.

|

| 2 OG Süd: 2. Ausstellungsraum: K3 |

|

Mit tiefsitzenden Männlichkeitsritualen beschäftigt sich die Performance K3: Ein grell beleuchtetes, weißes Leinen liegt in der Mitte des Bodens eines dunklen Raums. Zwei lange Holzstücke sind parallel zu den Rändern des Stoffes ausgelegt. Ein verzerrtes Geräusch von Peitschenhieben hallt durch den Raum. Der Rhythmus und das Schnalzen der Peitschenhiebe verlangsamen sich schließlich. In einer der Pausen tritt der Künstler, begleitet von einem Assistenten, aus dem Publikum nach vorne. Beide treten in das Schweinwerferlicht und entblößen ihren Oberkörper. Dann nehmen sie die Stöcke in die Hand und stellen sich für den Schlag auf. Im selben Moment schlagen sie sich gegenseitig mit aller Kraft auf den Rücken. Sie ziehen ihre Kleider wieder an und gehen weg. |

| 2 OG Süd: 2. Ausstellungsraum: Panta rhei |

|

U ISTE VODE STUPAMO I NE STUPAMO I JESMO I NISMO heißt übersetzt: „Wir steigen nicht zweimal in denselben Fluss“. Das Arrangement aus Gusseisen, Glas und Motoröl ist an einem Starkstromgerät angeschlossen: Auf diese Fläche, in dieses Wasser zu steigen, bedeutet Lebensgefahr. Kopljars Aktivierung des berühmten Heraklit-Zitats wird hier als lebensbedrohende Gefahrenzone ausgewiesen. Der überzeitliche Appell aus dieser Installation: Was aber ist zu tun, wenn wir spüren, dass sich die Geschichte dennoch zu wiederholen beginnt?

Zlatko Kopljar: Panta Rhei (Alles fließt), 1993, Gusseisen in Aluminium, Glas, Motoröl, Hochspannung,

|

| 2 OG Süd: 3. Ausstellungsraum: K14 |

|

Das postkommunistische Zagreb – eine Oase für Spekulanten im Kleid des (Post-)Kapitalismus: Zlatko Kopljar dokumentiert in K14, diesem poetischen Video, die sozialen Konflikte, die aus Immobilienspekulationen entstehen und viele Städte trifft. Sopnica Jelkovec ist ein neugebauter Stadtteil von Zagreb, der eigentlich ein sozialer Wohnbau hätte werden sollen. Schließlich, nach zahlreichen Pleiten, wurde das Viertel zu einem zwiespältigen Ort. Die Wohnungen wurden zu Vorzugspreisen an ethnische Minderheiten und andere gesellschaftliche Gruppen vermietet, die wenig gemeinsam haben. Da es an sozialer Infrastruktur und angemessenen öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln fehlt, bleibt das Viertel am Rande der Stadt isoliert. Zlatko Kopljar: K14, 2010,

|

| 2 OG Süd: 4. und 5. Ausstellungsraum: K13 |

|

Konkurrierende Konfliktfelder gegenwärtiger Weltwahrnehmung – wie Mikro- und Makropolitik, Lokalität und Globalität, Postkapitalismus und Postsozialismus, materialistische Haltung und metaphysische Haltepunkte – sind für Zlatko Kopljar die Schnittstellen seiner Kunst, denen er mit einem ästhetisch unbedingten Potenzial zu begegnen versucht. In K13 hat er – erstmals in diesen Räumen im steirischen herbst 2009 zu sehen – einen aus 300 Neonröhren bestehenden Lichtturm als Rauminstallation gebaut, dessen Licht sich gleißend über die Öffnung der historischen Gänge ergossen hat: Es ist die vorletzte Ausstellung in diesen Räumen vor dem damaligen Umzug gewesen.

Zlatko Kopljar: K13, 2009,

|

| 2 OG Süd: 6. Ausstellungsraum: K7 und K8 |

|

Zur Aufführung von K7 sehen die Zuschauer*innen im Saal eine Drei-Kanal-Projektion. Zwei Projektionen zeigen die zuvor gefilmten Videoaufnahmen des Künstlers, wie dieser durch den Wald streift und in seinem Keller inmitten von Gerümpel und Abfall herumtobt. Die dritte Projektion ist die Echtzeit-Übertragung der Performance des Künstlers im Nebenraum, bei der er sich kopfüber und regungslos in einen Haufen von Pillen und Federn legt.

Zlatko Kopljar: K7, 2001

|

| 2 OG Süd – Gang: K10 |

|

Im Gang des Südflügels im 2. Stock sind sechs Momentaufnahmen einer stundenlangen Aktion von Zlatko Kopljar aufgereiht, wie er auf den Hinterbeinen eines Stuhls schaukelt. K10 konfrontiert uns eine ganz einfache, triviale Aktion mit dem Körper und seiner Präsenz: Sie ist nicht etwas Sekundäres, sondern etwas, so Kopljar, in das man eindringen muss, um eine Frage zu stellen – „zum Beispiel nach Gott“. Der Prozess der De-Ontologisierung Gottes liegt für den Künstler nicht im Diskurs, sondern in der Präsenz des Körpers und seiner Regungen, im alltäglichen Atmen und in jeder Bewegung. Sich selbst in einen Ort ganz einzuschreiben und dort wirklich präsent zu sein: Das wäre Ontologie als Prozess. Es wäre jene Grenze, an der sich der erscheinende Körper und das unaussprechliche Wesen treffen könnten.

Zlatko Kopljar; K10, 2004, 6-tlg., Tintenstrahldrucke, Fotografie: Darko Bavoljak,

|

| 2 OG Süd: 7. Ausstellungsraum: K1, K6, K22 |

|

Im letzten (oder, von der Hautstiege aus im ersten) Raum des neu gestalteten Südflügels im 2. Stock ist die letzte und die erste „Konstruktion“ von Zlatko Kopljar versammelt: In einer Zeitspanne von mehr als 20 Jahren hatte der Künstler akribisch seine einzelnen Performances und Filme konzipiert. Als drittes Werk (K6) ist die persönlichste eingespannt: Ein schlichtes Foto dokumentiert eine Markierungs-Performance an jener Stelle, als sein Vater im Krieg durch eine Bombe – wie viele andere in jener Stadt – getötet wurde: 23091992. Zwei Wochen später war die Markierung durch darüberfahrende Autos ausgelöscht.

|

| 2 OG Flügel West: K2 |

|

„ICH BIN DER KÜNSTLER, DER DIE WELT VERÄNDERN WILL!“ Aus der Distanz eines ganzen Lebenswerks ist der Satz vielleicht selbstironisch. Als historisches Dokument ist er dennoch der Schlüssel zu Kopljars Werk: K2 entsteht in einer Galerie in Ostrava (Tschechische Republik): Auf dem Tisch in der Mitte des Raums liegen sieben Blätter Papier, auf jedem steht ein Wort aus dem genannten Satz. Der Künstler hebt ein Blatt nach dem anderen auf und hält es vor sein Gesicht, zeigt es dem Publikum und zerreißt es dann. Nachdem das letzte Wort vernichtet ist, nimmt er einen Schlegel unter dem Tisch hervor und beginnt, mit voller Kraft auf die Wände der Galerie einzuschlagen. Nach zwei oder drei Minuten sind auch die Zuschauer mit kleinen Hämmern ausgerüstet und beteiligen sich an der Zerstörung der Galerie.

Zlatko Kopljar, K2, 1997, Performance, Dauer: 10‘, (Videodokumentation 4‘ 49“), Kamera and Fotograf: Stanislav Cigoš,

|

| 1 OG Flügel Süd (Ost): K21 Random Empty |

|

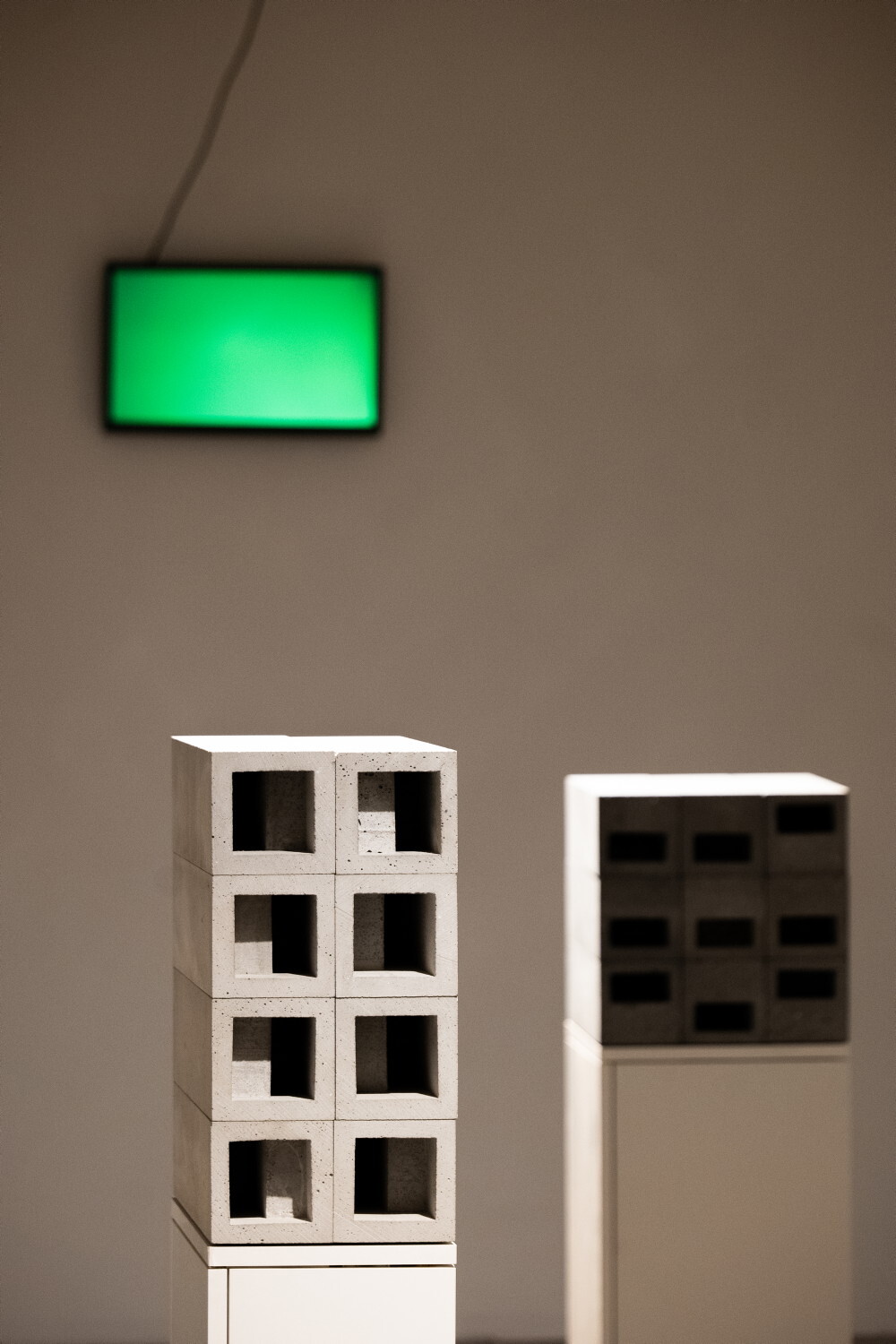

Einen Stock tiefer, (im ehemaligen Ausstellungsflügel Süd des KULTUM und nunmehrigen neuen Gästetrakt des Minoritenkonvents), sind im Gang zwei enigmatische Skulpturen ausgestellt, die konstruierte Leerräume aufweisen: Abermals Modelle aus Beton. Sie könnten Modelle für leerstehende Wohnungen sein, Behausungen des Sozialen und Existenziellen mit den darin sich ereignenden Nöten und Ängsten: „Zufällig leer.“ „Zufällig frei.“ Mit K21 Random Empty verabschiedet sich Zlatko Kopljar nämlich von seinen „K“s, den abstrakt klingenden Konstruktionen, mit denen er 1997 begonnen hat und in einer unvergleichlichen Weise den Künstler als Performer, Gestalter, Ermahner, Zerstörer, Zweifler, Heiler, Lichtbringer … vorgeführt hat. Auch das Video ist höchst abstrakt und zitiert die drei Grundfarben der digitalen Bildwahrnehmung: RED, GREEN, BLUE. Dazwischen aber ist nicht (mehr) Weiß – was die physikalische Wahrheit wäre – sondern das Schwarz.

Zlatko Kopljar: K21 Random Empty, 2017, 2 Betonobjekte, Full HD-Video loop,

|

| 1 OG Flügel West – Gang: K11 |

|

Auf dem Weg zur Leere, zur Auslöschung, hält Zlatko Kopljar in seinem „K“-Projekt an zahlreichen Stationen inne. Im Gang des Westflügels sind mit K11großformatige Fotoabzüge zu sehen, auf denen der Künstler Künstlerkollegen fotografisch porträtiert und inszeniert, die sich nie in den Mainstream einfügen wollten. Die meisten von ihnen sind schon tot. Sie blieben sich selbst immer treu, blieben damit aber auch am Rande der Gesellschaft, vernachlässigt und schließlich vergessen. Auch sie wollten die Welt verändern, doch die Welt hat sie nicht beachtet und gesehen. Kopljars Bildsprache ist radikal: Er stellt sie, die im Grunde Ähnliches wollten wie er, als gesellschaftlichen Abfall dar, als unerwünschte Menschen. Die Serie ist eine Radikalanklage gegen Tendenzen in einer kapitalistischen Kultur, die Umstände schafft, dass bestimmte Menschen an den Rand verbannt oder sogar ganz ausgeschlossen werden.

Zlatko Kopljar: K11, 2007, 7-tlg., Farbdruck auf Vinyl

|

| 1 OG West Zelle 4: K18 |

|

Die letzte in dieser Gestalt ist K18. Darin verabschiedet sich der Künstler als Lichtfigur, die mit K13 erstmals aufgetaucht ist. Er verabschiedet sich auch als jene „persona“, die als „Blitzableiter menschlicher Sehnsucht“ zum Ereignisort seiner künstlerischen, existenziellen, gesellschaftskritischen und transzendierenden Konstruktionen geworden ist. Die ganze Zeit über folgt die Kamera dem Bach im Wald. Am Ende des Films findet die Kamera den Tod als „Wesen“. Der Film schließt mit einem vibrierenden Rechteck in einem dunklen Wald und basiert auf der Frage: „Ist es nicht die Aufgabe eines Künstlers, sich ständig von der Kunst zu verabschieden?“ Der Sound klingt wie ein Geräusch oder wie Musik, es legt sich ein poetischer Text von Miloš Đurđević über die Abwesenheit, über den Tod und die Vergänglichkeit über die Szene |

| 1 OG West Raum 8: K12 |

|

Den ersten Tod erlebt der Künstler im schwarzen Anzug in K12. Das Doppelvideo, im Raum vor dem Cubus zu sehen, ist ein Wendepunkt in der Großerzählung von Kopljars Konstruktionen.

|

| 1 OG West Raum 7: "I believe", LOVE SHOT, K15 |

|

Das ist Glaube. Mehr als ein Jahrzehnt vorher, am Beginn seines öffentlichen künstlerischen Schaffens, rammt Zlatko Kopljar eine ganze Serie großer Nadeln in die Wand, ohne Zwirn, ohne Faden. Die Installation ist auf der Lehmwand im großen Ausstellungsraum im Westflügel vor dem Cubus aufgebaut: I believe ist ein „Bekenntnis“, das man als Kunstwerk selten findet.

|

| 1 OG West – Cubus |

|

Kopljars Verhandeln gesellschaftlicher Themen ist schließlich ein erschütternd in K17 nachzuvollziehen. Schauplatz ist New York. Der Künstler, der in seiner Großerzählung längst nicht mehr lebt, kehrt als Lichtfigur im Big Apple wieder. Ob als Engel oder Lucifer ist nicht ganz entschieden. Als Lebender (in schwarzem Anzug) war er fünf Jahre vorher in dieser Stadt gekniet, u.a. vor der Wall Street in New York (K9 compassion). Nach dem Börsenkrach 2008 – zu dieser Zeit kommt es zu Occupy-Bewegungen und Protesten auf der ganzen Welt – kehrt er also an denselben Ort zurück und setzt mit K17 ein erschütterndes Dokument gegen die Gier: „In diesem Projekt geht es um den dringenden Bedarf an Ethik im Bereich des globalen Finanzwesens“ (Zlatko Kopljar).

Zlatko Kopljar, K17, 2012,

|

| 1 OG Flügel Süd (West): K9 compassion |

|

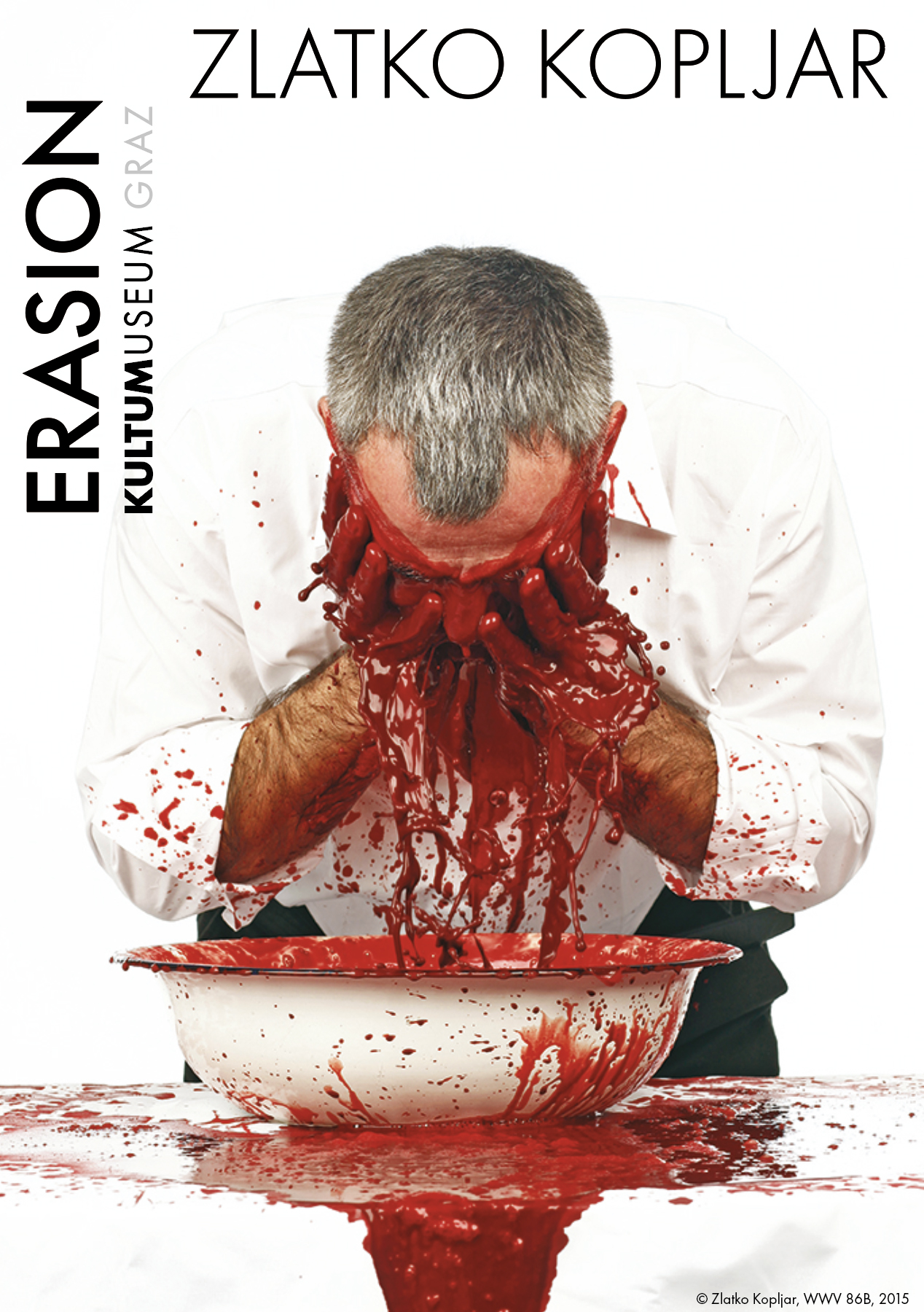

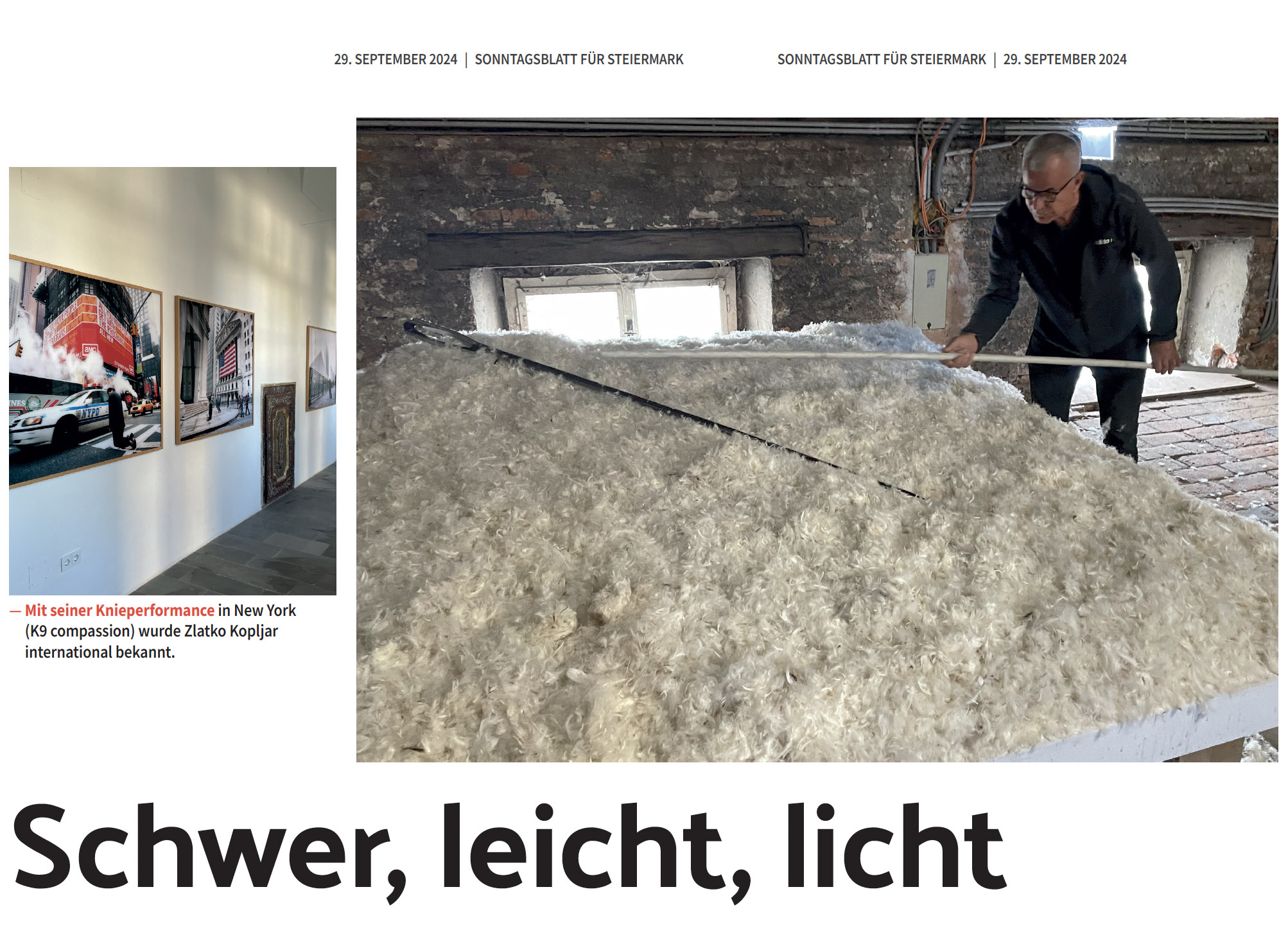

K9 compassion, die „Knieperformance“ in New York und anderen Zentren der Macht, für die Kopljar international bekannt geworden ist, ist im Südflügel hin zum Minoritensaal aufgereiht. Der Künstler kniet dabei auf einem Taschentuch, dem einzigen Stück Land, das er dabei hat.

Zlatko Kopljar: K9 compassion, 2004,

|

| 1 OG Minoritensaal |

|

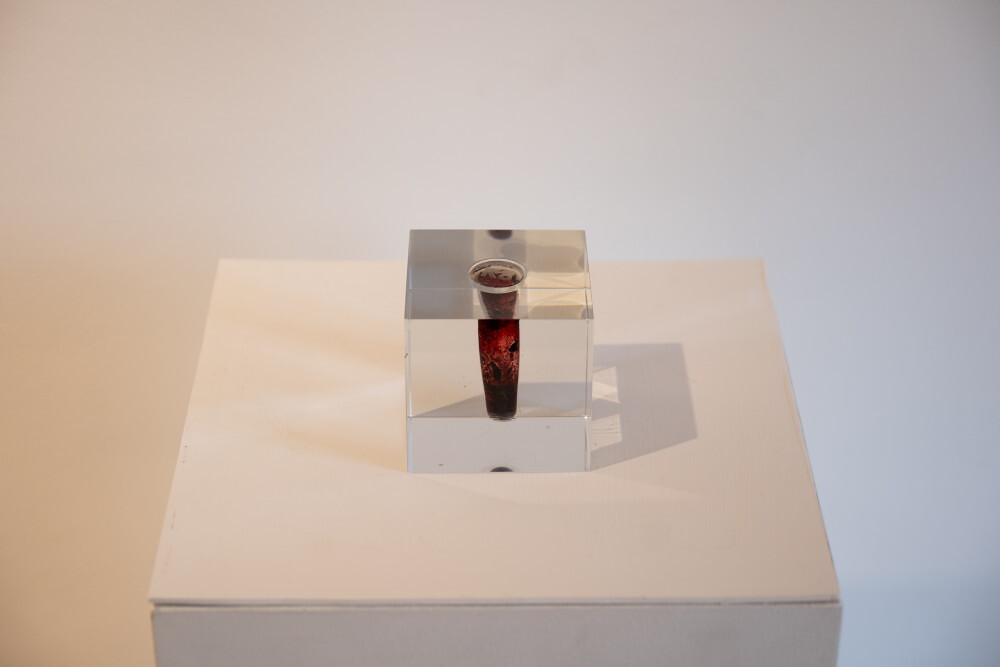

Mit unverhohlenem Pathos wird der barocke Minoritensaal in dieser Schau zusätzlich übersteigert: Die Stimme, die seinen Raum erfüllt, stammt aus der Schlusseinstellung von Andrej Tarkowskijs „Nostalghia“ (1983). Sie hält einen letzten Aufruf zum Zusammenhalt und ruft zur Umkehr auf. In der Predigt des „Verrückten“ Domenico auf dem römischen Kapitol werden die Irrwege der modernen Zivilisation angeprangert, bevor sich der Prediger auf dem Reiterstandbild Marc Aurels mit Benzin übergießt und im Wegrennen schließlich verbrennt. Auf der Lesekanzel ist ein kleiner Bildschirm positioniert, auf dem man nur ein Flimmern sieht: Die erste Version von K9, erstmals im „The Kitchen“ in New York gezeigt, ist durch und durch ikonoklastisch. In Wirklichkeit sind all jene zuvor genannten Orte zu sehen, vor denen Kopljar niederkniete, als Video, die später „K9 – compassion“ lauten. Doch die Bilder wurden digital zerstört und zwar nach einem strengen Muster, das aus der DNA des Blutes des Künstlers erzeugt wurde. Dieses Verfahren steigert noch einmal die existentialistische Brechung, die sich mit dem Anspruch dieser Geste der Unterwerfung verbindet. |

| 1 OG Süd Franziskussaal: Disturbances |

|

Fragen von Metaphysik sind bei Kopljars Werk ein durchgehendes Motiv über mehr als drei Jahrzehnte, er hat fast alle Varianten der künstlerischen Ausdrucksweise von Performance, Fotografie, Film, Skulptur, (Gedächtnis-)Kunst durchgespielt. Seit drei Jahren hat er sich entschieden, erstmals und nur mehr zu malen. Konsequent vermeidet er dabei jede offene Botschaft. Es sind „Streifenbilder“, die aber bei näherem Hinsehen eine durchaus subjektive Malgeste offenbaren, womit er sich auch von der Auslöschung des Künstler-Ichs distanziert. Nach dem Abschluss seiner „Konstruktionen“ im Jahr 2019 entwirft sich Zlatko Kopljar – in den Lockdown-Phasen der Covid19-Pandemie – als Künstler neu. Er mietet sich erstmals ein Atelier in Zagreb und besinnt sich dem, was er bis 1991 in Venedig auch studiert hat: der Malerei. Seit seinem Studienabschluss ist er nämlich nie mehr als Maler vor die Öffentlichkeit getreten. Seine seit 2021 entstehenden Gemälde sind das erste Mal überhaupt in dieser Ausstellung – in zehn großformatigen Gemälden – zu sehen.

Zlatko Koplljar: Disturbances, 2021–24, 10 tlg., Öl auf Leinwand, Ausstellungsansicht: Zlatko Kopljar: AUSLÖSCHUNG | ERASION. KULTUMUSEUM GrazAuf den ersten Blick knüpfen seine Gemälde in der abstrakten Farbfeldmalerei der 1960er und 1970er Jahre an. Ein genaueres Hinsehen auf die malerische Gestaltung seiner Gemälde verrät freilich mehr. Ging es dort um die Auslöschung der künstlerischen Handschrift, sind die Farbstreifen in Zlatko Kopljars in Wirklichkeit höchst erzählerisch: In einem kleinen Farbausschnitt der einzelnen Farbstreifen kann man die stunden-, tage- und wochenlange Arbeit des Malers Zlatko Kopljar erahnen. Er macht seither tatsächlich nichts anderes, als täglich auf diese Art zu malen. Dass er die Malereien „Störungen“ nennt, zeugt von der Brücke zu seinem bisherigen Lebenswerk.

Zlatko Koplljar: Disturbances, 2021–24, 10 tlg., Öl auf Leinwand, Ausstellungsansicht: Zlatko Kopljar: AUSLÖSCHUNG | ERASION. KULTUMUSEUM Graz

Doch gleichzeitig ist das Anknüpfen an Vorbilder wie Mark Rothko oder Barnett Newman – ihre Bücher findet man nicht ganz zufällig im Atelier – auch ein Statement, dass es für die Hereinholung des Undarstellbaren als des Sublimen und Erhabenen in unserer Gesellschaft höchste Zeit ist: Kopljar hat zum Zustand der Welt in seinen Konstruktionen dazu genug gesagt und auch Vorstellungen unterbreitet. „Auslöschung“ ist schließlich nicht nur als (Zer-)Störung zu deuten, sondern auch als ein Löschen von dem, was war, hin zu einer neuen Schau. |

| 1 OG Süd Galerie |

|

Auslöschung gilt für den Künstler schließlich auch dem Ort der Präsentation von Kunst. Ihn profund zu hinterfragen ist als Epilog der Ausstellung demnach gebündelt auch in der Frage nach dem Sinn eines Museums – dem typischen Aufbewahrungsort für die Bilder: In K4 versperrt Kopljar 2002 das damalige Museum für zeitgenössische Kunst in Zagreb in einer nächtlichen Aktion mit einem 12 Tonnen schweren Betonblock, in K20 Empty gießt er die Volumina des MoMA in New York und der Tate Modern in London in Betonmodelle, die die letzten Werke auf der Galerie des letzten Raums der Ausstellung im Südflügel bilden. Sie geben kein Inneres frei. Ihre Volumina sind auch als Reliquiare zu deuten, die mit den gleichen Modellen 2018 enstehen: Diese waren erstmals bei „Glaube Liebe Hoffnung“ im Kunsthaus Graz ausgestellt und wurden damals für die Sammlung des KULTUM erworben. |

ZLATKO KOPLJAR: ERASION (Works from 1990–2024)

At a time of deeply felt crises and new wars, the work of Croatian artist Zlatko Kopljar is an artistic example of an ethical and aesthetic (re)orientation: Kopljar explores the lasting after-effects of the traumas of the 20th century for the present day and subjects them to artistic transformation. In co-production with steirischer herbst ‘24, the KULTUMUSEUM Graz is showing a retrospective of the artist's work spanning a period of 30 years.

The brick tower in the inner courtyard of the Minorite Monastery in Graz was the most outwardly visible of the 22 “Constructions” by Croatian artist Zlatko Kopljar that were exhibited on three floors at steirischer herbst 24 in the KULTUM: Following the major retrospective at the MSU1 in Zagreb in 2019/20, it was the artist’s largest retrospective to date, which was expanded in Graz with the series of iconoclastic paintings created in recent years—referred to as “Disturbances”. With this show, the artist is handing over the majority of his multimedia work to the collection of the KULTUMUSEUM Graz, which focuses on how dimensions of religion appear in contemporary art.

The fruitful, sometimes disturbing relationship between ethics and aesthetics is at the centre of this important work by Zlatko Kopljar for our collection, which occupies its own museum space in the hitherto imaginary museum project of ‘No Museum Has God ’2. And with it the question of what role the artist can play in the socio-political balance of power with all its distortions and what answers he can provide for society. Kopljar’s answer is existentially condensed and politically demanding, even global at the same time. At times it has the traits of a lonely prophet, a tireless preacher against forgetting, then again of a global pilgrim in front of the power centers, at times even of a messianic figure of redemption and light. One finds elementary expressions of faith (I believe), prayer (DSASFSI,UE?) and forgiveness (K6) as well as those of despair (K7) and the darkest abyss. In his work, Kopljar deals very early on with the themes of guilt and sacrifice after the experience of war. The rituals of purification (Sacrifice) search for ways to erase these deeds. There is a direct Braille version of the Apocalypse (Vinculum II), references to apocalyptic farewell speeches (K9), pacifist “love shots” (Love Shot) or rituals of purification and absolution (Sacrifice): The beginning of Zlatko Kopljar’s artistic path coincided with the years of the Croatian War of Independence, which is called the “Balkan War” in Western parlance, but which is far too unspecific for the artist: “We were attacked. No one helped us back then; instead of weapons, the EU sent us an embargo. “3

So the angel of help did not materialize—this association was made in one of several artist talks before a re-enactment of a historical “Abraham’s sacrifice” according to Gen 22 (Sacrifice of Isaac) from 1993. But even then, a motif was foreshadowed that would carry Zlatko Kopljar through the following decades of his life: Resistance, resisting false myths of victimization, his resistance—against systems of constricting or freedom-robbing power. He refers not only to politics, but also to art: he will block the former MSU (Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb) with a 12-ton concrete block in the K4 action. He will proclaim the two concrete models of the MoMA in New York and the Tate Modern in London as “empty” (K20 Empty) or call them “Reliquary”: Museums should exhibit the art of artists, not that of curators. The motif of resistance will largely characterize Kopljar’s art, but it is paired with strange words, such as “pity”, “emptiness”, ultimately even “failure”.

Kneeling, of all things, is the strongest motif of resistance in Kopljar’s work; he did this for the first time in New York (K9 compassion), and later worldwide in front of other important buildings of power (K9 compassion+).Kopljar carried out the last of these kneeling performances for the time being on the polished stone surface of Franjo Tudjman’s grave: K9 compassion at home.

The presentation of almost the entire artistic oeuvre of Zlatko Kopljar in Graz took place in the partner program of steirischer herbst 24 with his theme “HORROR PATRIAE”, in a political election year that has seen the threatening rise of populist, in some cases far-right parties both locally and internationally. Kopljar is constantly revisiting his personal “Horror Patriae” in a wide variety of media, which is also a general and topical issue—not just for Austria, but for Europe as a whole.

The artist extends his own trauma, based on the wars in the then disintegrating Yugoslavia, to the traumas of the 20th and 21st centuries. His questions are becoming increasingly topical. The fact that the brick tower mentioned at the beginning of the exhibition rests on euro pallets cast in aluminum is a symbolic reference to the fact that the current political shift to the right in Europe has become a European problem. He was finally quoted resignedly in the TV report on this exhibition on ORF: “I’ve had enough of certain things from our past, because they are happening again, but on a much larger scale. I’ve had enough. I can’t start my work all over again. “4

So what Kopljar has done: To explore the concepts of fascism and its extermination machine, subsequent communism and capitalism with their late consequences and successors, and—dare I use the stiff word—to transcend them artistically. His recurring question in life is: “What role does the artist and art itself play in all these fields?” Even if he—or she—should fail in the end, the artist goes through a dialectic within the framework of his creative processes and the images evoked from them, which should be particularly emphasized here. What unites all these processes and images in Zlatko Kopljar’s work has an ambiguous intersection with the exhibition theme of ERASION.

This brings me back to the opening image (K19): in many cases, the memory that the artist is defending himself against has also been erased: The bricks mentioned were made by forced laborers from a former concentration camp in Jasenovac (where just as many people were killed as in Mauthausen in Austria)—there is blood on them. Their makers, both men and women, were literally wiped out in the concentration camp. The traces of his father’s violent death are erased after a few weeks (K6). The sight of the blind people in Kopljar’s performances is erased (but they see more in the end) (K1): Even the first of his constructions bears this signature.

Kopljar erects a monument to the artists of his Croatian homeland who have been erased from the public consciousness and recognition in the large-format photo series of K11. After his own erasion in K12, he encounters the light: he goes to the source of the light and becomes a figure of light (K13 to K18). Subsequently, he will accompany political aberrations (K14), iconic memories (K15), historical anamneses (K16) and current processes of greed, illuminate them with his aura or be helplessly at their mercy (K17): The fact that he stands lifted above the skyscrapers of New York, in the corner and is ashamed, is the last appearance of the light figure before it is finally disembodied in the course of nature in K18—erased.

After the brick towers (K19) and the concrete models that followed, Kopljar finally bid farewell to this form of art and began a phase as a painter. These paintings, which have been created since 2021, were shown for the first time in this exhibition. They are convincing precisely because of the EXPLOSION of their imagery: now it is about the experience of the sublime, perhaps also about the incursion of the absolute—especially in the disturbances: the paintings are called “Disturbances”. They evoke associations of peace, spirituality and the sublime.

What can art contribute to important social issues? Zlatko Kopljar has actually dedicated his entire life’s work to this question. He appeals to the distinction between good and evil, he believes in ethical action. He is not naïve, on the contrary. He relies on the power of the subject and believes in presence—even after its erasion. His work is now part of our museum. I am very pleased about this and thank the artist for the trust he has placed in us to carry his work into the future.

Johannes Rauchenberger

Zlatko Kopljar: Object, 1990, Edelstahl, Honig,

Zlatko Kopljar: Object, 1990, Edelstahl, Honig,